|

|

|

|

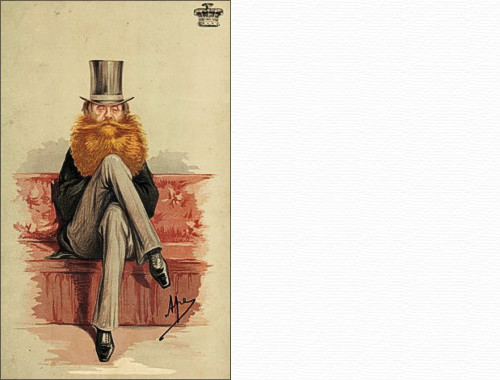

| Carlo Pellegrini (Ape) William Hepworth Dixon, Vanity Fair 1872 |

|

|

|

|

Il crescente numero di riviste nella seconda metà dell’Ottocento aumentò la domanda di buoni illustratori. Per alcuni artisti, quello di illustratore era un mestiere vero e proprio, e ben remunerato. Per altri, invece, era solo un modo di arrotondare i guadagni. Secondo il pittore George du Maurier, vignettista satirico di “Punch”, l’illustrazione era la gallina dalle uova d’oro.

Così “Vanity Fair”, una rivista lanciata nel 1868, attirò la mano mordace di Carlo Pellegrini, inventore di uno stereotipo imitato da diversi caricaturisti inglesi, ma anche l’artista macchiaiolo Adriano Cecioni, Melchiorre Delfico e Libero Prosperi. Tra i loro illustri colleghi figuravano James Tissot e Leslie Ward.

Anche altri italiani contribuirono a periodici d’attualità. Tra il 1893 e il 1898, Ettore Tito collaborò a “The Graphic” con disegni raffiguranti scene di vita contemporanea a Londra, Venezia e in Svizzera. Gennaro d’Amato lavorò per lo stesso periodico e a fine secolo anche come inviato speciale per “The Illustrated London News”, guadagnando talmente tanto da far scoppiare d’invidia Antonio Mancini, che si trovava a Londra nello stesso periodo. Un altro napoletano, Fortunino Matania, illustrò l’incoronazione di Edoardo VII nel 1902, e poi tutti gli eventi a cui partecipò la famiglia reale, fino all’incoronazione di Elisabetta II nel 1953. Nel 1904 fu accolto nella redazione di “The Sphere” e fece anche dei reportage durante la Grande Guerra.

Negli ultimi cinque anni del secolo, Domenico Morelli, Francesco Paolo Michetti e Giovanni Segantini furono invitati a contribuire con alcune tavole alla Bibbia di Amsterdam, un’iniziativa editoriale internazionale, presentata in anteprima a Londra nel 1901 e molto elogiata dalla stampa britannica. Nel 1885 Keningale Cook chiese a Telemaco Signorini l’autorizzazione di utilizzare, per una pubblicazione inglese, gli stampi creati dall’artista per una sua autobiografia italiana. A Edoardo de Martino, invece, fu commissionata una serie di riproduzioni per una storia della marina militare britannica, uscita su “The Graphic” dal 1894 al 1897. Comunque, chi riuscì meglio come illustratore di vedute italiane per l’editoria inglese, fu senz’altro Alberto Pisa. Le sue opere continuarono a essere riprodotte su libri di ampia diffusione, fino al Novecento avanzato.

|

|

|

The increasing number of periodicals published in the second half of the nineteenth century fuelled the demand for good illustrators. For some artists, illustration was simply a means of rounding up their earnings, for others it was a serious and well-paid occupation: according to George du Maurier, a satirical cartoonist of “Punch”, illustration was the goose that laid the golden egg.

Thus “Vanity Fair”, founded in 1868, attracted the caustic pen of Carlo Pellegrini, who invented a stereotype imitated by many an English caricaturist, together with the Macchiaiolo artist Adriano Cecioni, Melchiorre Delfico and Libero Prosperi: their illustrious colleagues included James Tissot and Leslie Ward.

Other Italians also contributed to periodicals of current events. Between 1893 and 1898, Ettore Tito submitted a considerable number of illustrations to “The Graphic” regarding contemporary scenes of London, Venice and Switzerland. Gennaro d’Amato worked for the same magazine towards the end of the century, and as special correspondent for “The Illustrated London News”. The money he made aroused the envy of Antonio Mancini, who found himself in London in the same period. Another Neapolitan artist, Fortunino Matania, illustrated the coronation of Edward VII in 1902, and then all the public events involving the Royal Family, up to the coronation of Elizbeth II in 1953. In 1904, he was employed by the editorial board of “The Sphere” and was engaged in reportage during the First World War.

Towards the end of the century, Domenico Morelli, Francesco Paolo Michetti and Giovanni Segantini were invited to contribute plates for the Amsterdam Bible, an international editorial initiative, a preview of which was presented in London in 1901 and covered with enthusiasm by the British press.

In 1885, Keningale Cook asked Telemaco Signorini for authorisation to utilise, for publication in Britain, the moulds the artist had already created for his own autobiography in Italy. In another instance, Edoardo De Martino was commisioned to make a series of reproductions for a history of the Royal Navy, which “The Graphic” published from 1894 to 1897.

However, the artist who met with most success, as illustrator of Italian views for publication in England, was without doubt Alberto Pisa: his works continued to be reproduced in books of wide circulation well into the twentieth century.

|

|

|

|

|

|